Did you know Warren G is still alive?!? I obviously confused Nate Dogg with Warren G. How embarrassing. Anyways, on to the topic at hand…regulators, mount up.

So what exactly is the difference between a load-step and a sub-step? A load-step should be thought of as a set of constraints/loads that are being solved for while the sub-steps are how you transition from one loading environment to the next.

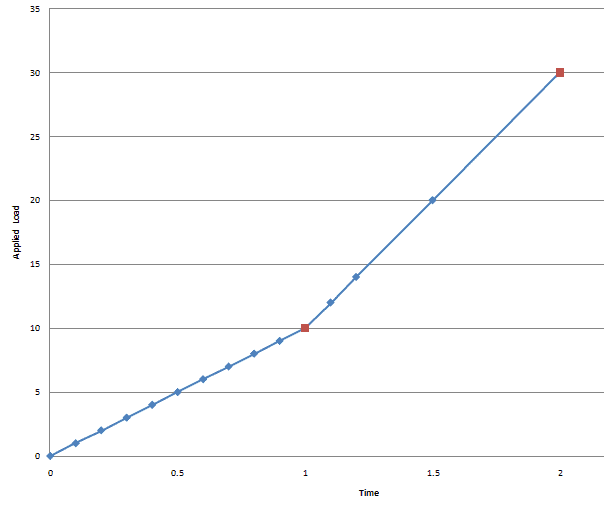

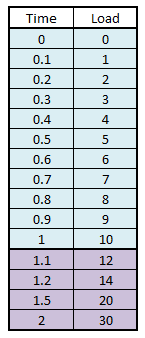

So as shown in the graph above, at time=1 (for a static run time is meaningless, think of it more as a % of applied load where 1=100%) the applied load is 10 pounds. Since it’s the first load-step, all applied values are ramped from 0 (by default), and there are 10-equal interval sub-steps that allow the solver to get from 0 to 10. For load-step 2, which has an end time of 2 (load-steps must have increasing end-times), only 4 sub-steps that get progressively larger were used. We’ll get into how that works, but the important take-away is that load-step 2 starts at the end of load-step1.

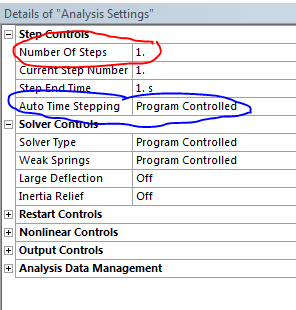

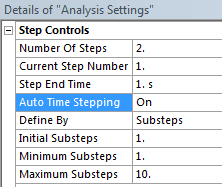

Within Mechanical, you define both load-step and sub-step controls in the ‘Analysis Settings’.

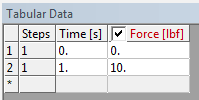

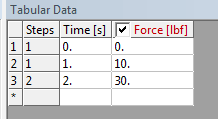

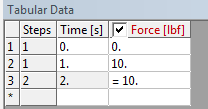

By default the number of steps in an environment is 1, and the solver has control over how the loads are ramped. As soon as you increase the number of steps you will see this reflected in the ‘Tabular Data’ window for any applied load or constraint.

When you first start defining the load for a multi-load-step analysis, Mechanical assumes that the loading will remain constant for all subsequent steps. This is indicated by an ‘=’ sign shown in the tabular data.

So after you’ve gone through and defined an assembly loading process, large deflection plastic analysis to determine permanent set, or whatever else your heart desires…you can go back to define how the loads are ramped from one step to the next.

Toggling the ‘Auto Time Stepping’ to ‘On’ gives you even more options.

You have the ability to define the ramping controls either by number of sub-steps or time. Both represent the same thing, just presented through a different paradigm.

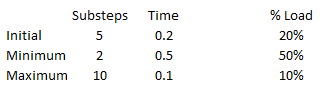

Before I get into the difference between sub-step and time, I’ll touch on the Initial/Minimum/Maximum values (note the following explanation is valid for the sub-step paradigm). The initial value is the initial ramping value used to start off the current load step. If the solver was able to converge easily, it can increase the load increment until it hits the ‘minimum’ sub-step value. If the sub-step was difficult to solve, or did not solve at all, the solver can reduce the increment and try again.

Assuming the end time of the load step is 1, here are equivalent sub-step controls (sub-step vs time) listed next to what the actual load increments are:

One thing to note is that if you were to change the end time from 1 to 2, the sub-step-method would still ramp by the exact same amount for each sub-step whereas the time-method would ramp it slower. Obviously if you are running a transient analysis these controls become very important as they determine what response frequencies you’ll pickup from your structure. The documentation recommends a time-step size of (1/20*f), where f is the highest frequency assumed to contribute to the response. If your time-steps are too large, you’ll miss the higher frequency content that could be more damaging.

So now you’re probably thinking “great, so now what?”. First…watch that tone mister. Second, this should be one of the first places you should turn when you run into model convergence issues. If a model is poorly constrained you can run a first load-step with additional constraints and then ‘release’ it once the model has converged. If you have a model held in place purely by contact you can run an initial no-applied-load-step to allow the contacts to ‘settle down’ and properly engage. If you have a model that fails due to excessive distortion or accumulated plastic strain you can increase the number of sub-steps to ramp the loads slower. Or you could use this information to create some fairly complex loading environments.

I’ll be going over all of this information and more (activating/deactivating loads, command snippet use, etc) in the upcoming PADT Webinar being held on November 17th. Hope to see you there.