Editor’s note: Unfortunately this post and a few others were the victim of database munging that resulted in the images being lost. We are trying to recover them. We hope that you find the text useful even without the images.

ULTEM-9085 is one of my favorite materials to 3D-print: one of the reasons is it is a high performance polymer that can and has been used for end part manufacturing (see my blog post about ULTEM in functional aerospace parts), but the other is because it is a demanding material to print, in ways that ABS, Polycarbonate and even Nylon are not. What makes it demanding is primarily that ULTEM supports are not soluble and need to be removed mechanically. An additional challenge comes from the fact that the support is best removed when the part is at a high temperature (175-195 C), which requires the use of gloves and reduces the user’s dexterity. For complex geometries with internal channels, this is particularly challenging and occasionally results in an inability to print a certain part in ULTEM-9085, which runs contrary to the design freedom this technology otherwise enables.

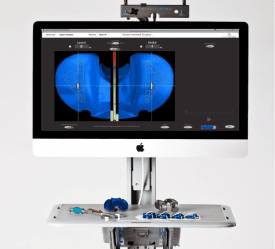

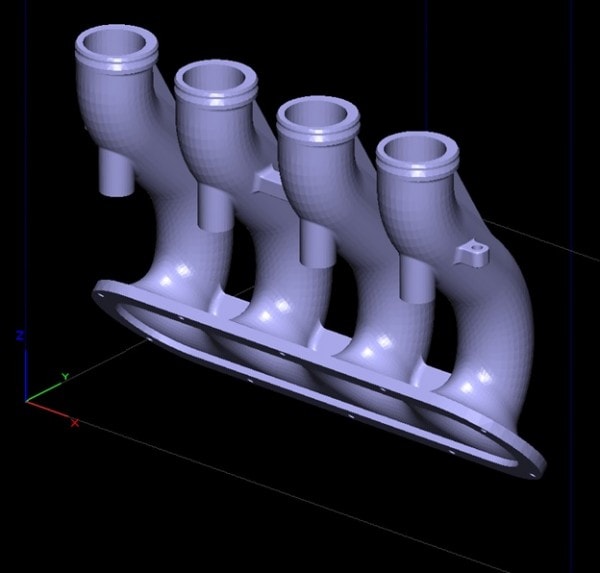

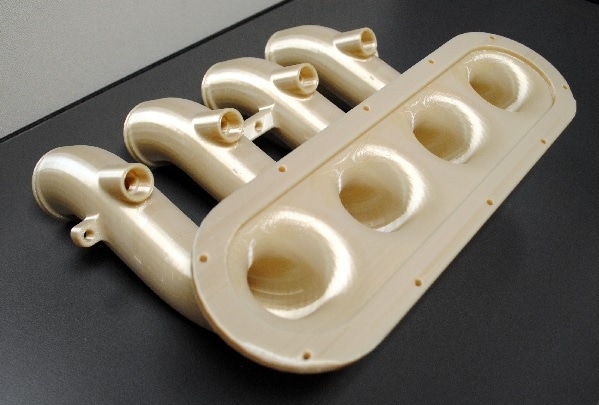

In this post, I accumulate what I have learned through working (and failing) on many an ULTEM-9085 job, as well as through discussions with other users, and share this here in terms of design and process guidelines. To demonstrate these guidelines, I use a recent geometry that we printed for the Arizona State University’s (ASU) SAE team for an engine intake manifold. These guidelines apply to the Stratasys Fortus platform (for Fused Deposition Modeling, or FDM) using the Insight software that accompanies these tools. The screen shots are from Insight 10.6, and a Fortus 400 was used to print the parts shown.

Summary of Guidelines:

- Orient the part to eliminate supports in regions where you cannot remove them

- Use the box support style

- Optimize parameter settings (support angle, contour width, layer thickness)

- Remove the supports as soon as the part comes out of the build chamber

- Other observations: the interface of separation

1. Part Orientation

The single most important factor in simplifying support removal is part orientation. Most users of the FDM process know that part orientation determines the amount of support material consumed and also impacts the time to build the part. When working with ULTEM-9085, the additional challenge is that it is possible to design in supports that cannot be removed and will require you to scrap the job. This is especially true of internal features. While the automatic orientation feature in Insight allows you to minimize supports, it does not account for the difficulty of removing them. Thus when you are dealing with internal features, you may need to manually orient your part such that the internal features are aligned as close to the vertical as possible, and above the support angle (to be covered later).

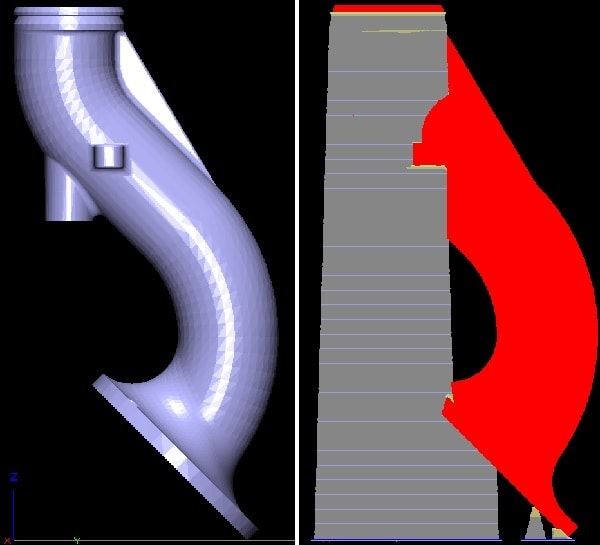

As shown in Figure 1, for the intake manifold, I oriented the internal pipe structure close to the vertical and had to iterate a few times and verify that I had no support in the hard-to-reach areas. While I did have supports internally, they were limited to areas that were easy to access.

2. Box Supports

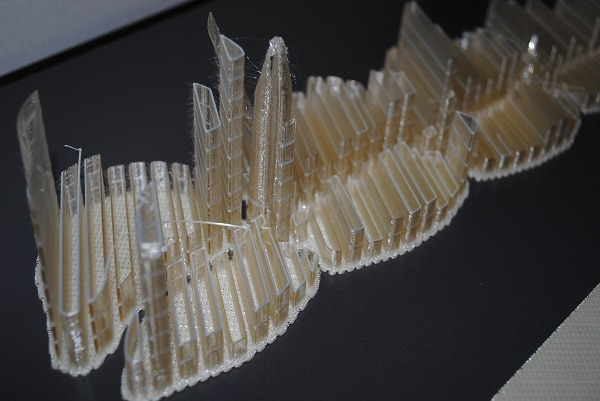

In a recent software upgrade, Insight added the ability to create box supports. The support structures consist of adjacent boxes instead of a continuous raster, which has the effect of allowing for easier separation of the support, though does slow down the build time. In my experience this support strategy does help with removal – the one parameter to consider here is the “Perforations” setting, though the default values were used for this part. The perforation is a layer of model material that is inserted into the support to make for easier breaking off of the support material. All cleavage surfaces in Fig. 3 are at perforation edges and you can see the building like construction with each floor distinguished by a layer of model material. When you have supports in hard to access regions, consider increasing the interval height so as to ensure you get separation at the model-support interface on the part before it occurs within the support on a perforation layer.

3. Optimize Process Parameters

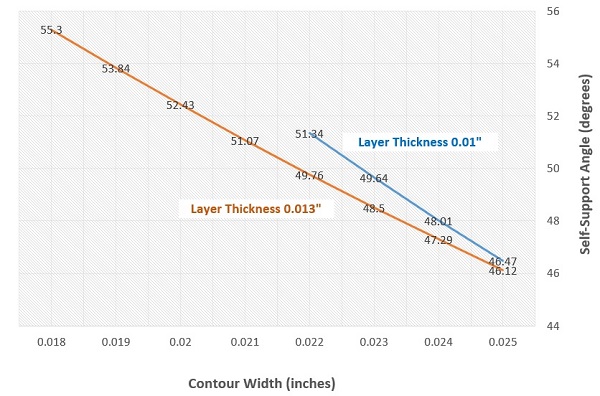

While orientation will have the most significant impact on the support you need, another variable to be aware of is the “Self-Support Angle” parameter. This angle is measured from the horizontal, and represents the minimum angle of the part wall that will be built without supports. As a result, to reduce support requirements, you want this number to be as low as possible so that a greater volume of the part can be self-supported. Stratasys recommends default values, but these scale as a function of the contour width, and layer thickness, as shown in Fig. 4. The values bottom out at 40 degrees for the 0.013″ layer thickness and 43 degrees for the 0.010″ layer thickness. Thus, all other things being equal, you will be able to reduce the support needed by choosing a 0.013″ layer thickness and a 0.026″ or larger contour width. Note that both of these will impact your ability to resolve thin walls and fine features, so ensure you scan through all the tool-paths to validate that the geometry is accurately filled in.

4. Remove Supports Immediately

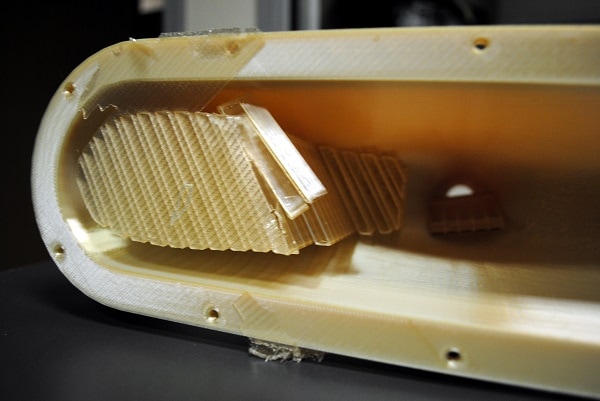

Supports are best removed when the model-support interface is hot. The best time to do this is right after you remove the parts from the print chamber, which is held at 195 C for ULTEM-9085. Ensure you have safety glasses on, work with thermal gloves and have a plier handy to pull out the support. In theory the parts can be re-heated again (175 C is a reasonable value for the oven), but Stratasys suggests that each re-heat cycle actually strengthens the interface, making it harder to remove. As a result, the best time to remove the supports is immediately out of the printer. Figure 5 shows the results of support removal for the intake manifold parts, including the build sheet.

5. Other Observations: the Interface of Separation

It helps to visualize what we are trying to do when we remove supports. There are two interfaces in question here, as shown in Figure 6. One is the model-support interface, the other is the support-box structure interface. We need separation at the model-support interface since removing the thin piece of interface material can prove challenging if the box supports have broken off (as happened for the piece below). What this means is as you remove support, you need to not just pull the supports but also add some peeling force that creates the separation. Once you create separation at the correct interface, you can pull the supports and should have proper cleavage.

One final point to keep in mind is that in some cases, eliminating internal supports may be impossible, as shown for a different part in Figure 7 below. The point is to eliminate the support in places you cannot reach with your pliers and get enough peeling force applied to. In the case below, I chose to have supports at the wide opening since I had adequate access to them. With practice, you will get a better sense of what supports can and cannot be removed and use that intuition to better shape your design and process layout decisions before you print.

Show your support for ASU’s Formula SAE team at their Facebook page and see a video about the endeavor here.