What types of cellular designs do we find in nature?

Cellular structures are an important area of research in Additive Manufacturing (AM), including work we are doing here at PADT. As I described in a previous blog post, the research landscape can be broadly classified into four categories: application, design, modeling and manufacturing. In the context of design, most of the work today is primarily driven by software that represent complex cellular structures efficiently as well as analysis tools that enable optimization of these structures in response to environmental conditions and some desired objective. In most of these software, the designer is given a choice of selecting a specific unit cell to construct the entity being designed. However, it is not always apparent what the best unit cell choice is, and this is where I think a biomimetic approach can add much value. As with most biomimetic approaches, the first step is to frame a question and observe nature as a student. And the first question I asked is the one described at the start of this post: what types of cellular designs do we find in the natural world around us? In this post, I summarize my findings.

Design Strategies

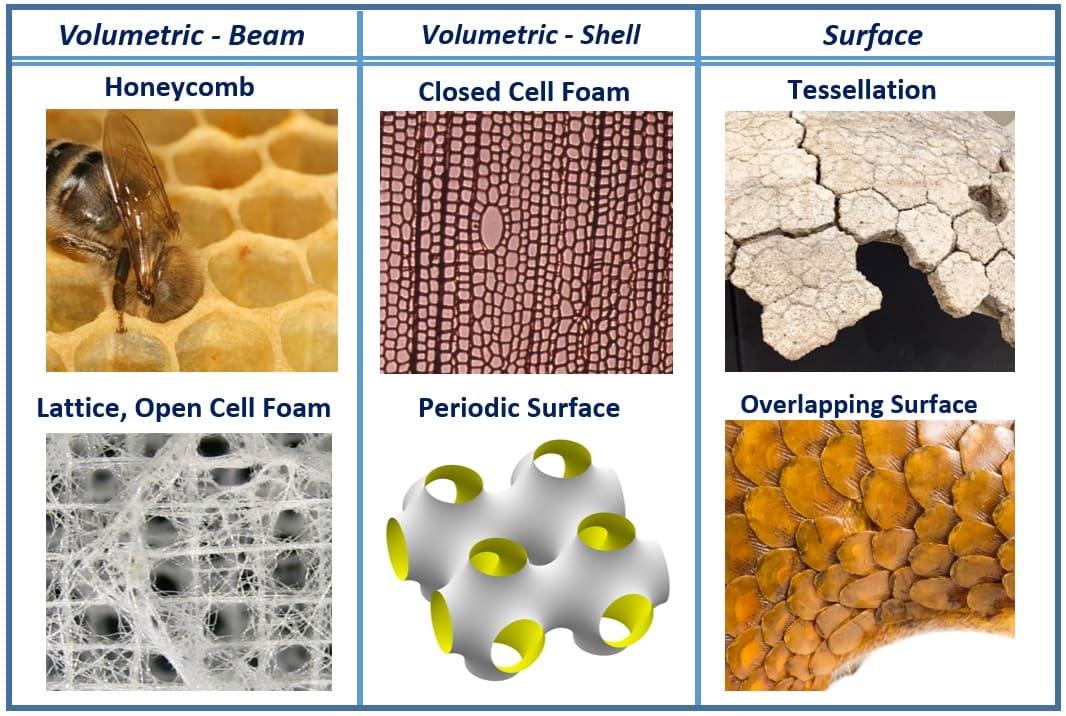

In a previous post, I classified cellular structures into 4 categories. However, this only addressed “volumetric” structures where the objective of the cellular structure is to fill three-dimensional space. Since then, I have decided to frame things a bit differently based on my studies of cellular structures in nature and the mechanics around these structures. First is the need to allow for the discretization of surfaces as well: nature does this often (animal armor or the wings of a dragonfly, for example). Secondly, a simple but important distinction from a modeling standpoint is whether the cellular structure in question uses beam- or shell-type elements in its construction (or a combination of the two). This has led me to expand my 4 categories into 6, which I now present in Figure 1 below.

Setting aside the “why” of these structures for a future post, here I wish to only present these 6 strategies from a structural design standpoint.

- Volumetric – Beam: These are cellular structures that fill space predominantly with beam-like elements. Two sub-categories may be further defined:

- Honeycomb: Honeycombs are prismatic, 2-dimensional cellular designs extruded in the 3rd dimension, like the well-known hexagonal honeycomb shown in Fig 1. All cross-sections through the 3rd dimension are thus identical. Though the hexagonal honeycomb is most well known, the term applies to all designs that have this prismatic property, including square and triangular honeycombs.

- Lattice and Open Cell Foam: Freeing up the prismatic requirement on the honeycomb brings us to a fully 3-dimensional lattice or open-cell foam. Lattice designs tend to embody higher stiffness levels while open cell foams enable energy absorption, which is why these may be further separated, as I have argued before. Nature tends to employ both strategies at different levels. One example of a predominantly lattice based strategy is the Venus flower basket sea sponge shown in Fig 1, trabecular bone is another example.

- Volumetric – Shell:

- Closed Cell Foam: Closed cell foams are open-cell foams with enclosed cells. This typically involves a membrane like structure that may be of varying thickness from the strut-like structures. Plant sections often reveal a closed cell foam, such as the douglas fir wood structure shown in Fig 1.

- Periodic Surface: Periodic surfaces are fascinating mathematical structures that often have multiple orders of symmetry similar to crystalline groups (but on a macro-scale) that make them strong candidates for design of stiff engineering structures and for packing high surface areas in a given volume while promoting flow or exchange. In nature, these are less commonly observed, but seen for example in sea urchin skeletal plates.

- Surface:

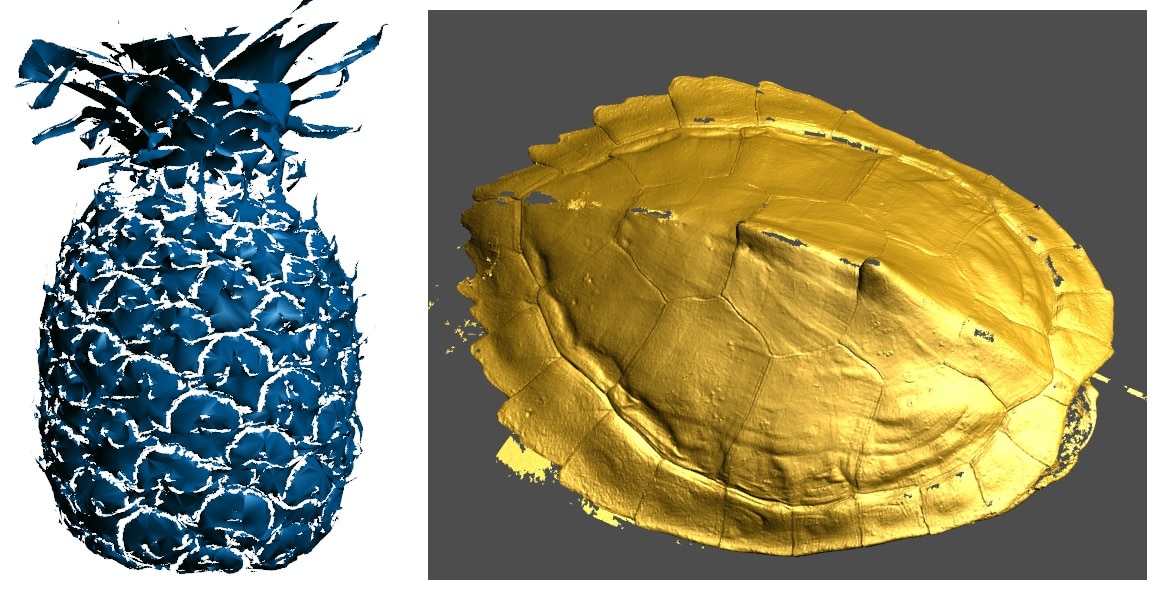

- Tessellation: Tessellation describes covering a surface with non-overlapping cells (as we do with tiles on a floor). Examples of tessellation in nature include the armored shells of several animals including the extinct glyptodon shown in Fig 1 and the pineapple and turtle shell shown in Fig 2 below.

- Overlapping Surface: Overlapping surfaces are a variation on tessellation where the cells are allowed to overlap (as we do with tiles on a roof). The most obvious example of this in nature is scales – including those of the pangolin shown in Fig 1.

What about Function then?

This separation into 6 categories is driven from a designer’s and an analyst’s perspective – designers tend to think in volumes and surfaces and the analyst investigates how these are modeled (beam- and shell-elements are at the first level of classification used here). However, this is not sufficient since it ignores the function of the cellular design, which both designer and analyst need to also consider. In the case of tessellation on the skin of an alligator for example as shown in Fig 3, was it selected for protection, easy of motion or for controlling temperature and fluid loss?

In a future post, I will attempt to develop an approach to classifying cellular structures that derives not from its structure or mechanics as I have here, but from its function, with the ultimate goal of attempting to reconcile the two approaches. This is not a trivial undertaking since it involves de-confounding multiple functional requirements, accounting for growth (nature’s “design for manufacturing”) and unwrapping what is often termed as “evolutionary baggage,” where the optimum solution may have been sidestepped by natural selection in favor of other, more pressing needs. Despite these challenges, I believe some first-order themes can be discerned that can in turn be of use to the designer in selecting a particular design strategy for a specific application.

References

This is by no means the first attempt at a classification of cellular structures in nature and while the specific 6 part separation proposed in this post was developed by me, it combines ideas from a lot of previous work, and three of the best that I strongly recommend as further reading on this subject are listed below.

- Gibson, Ashby, Harley (2010), Cellular Materials in Nature and Medicine, Cambridge University Press; 1st edition

- Naleway, Porter, McKittrick, Meyers (2015), Structural Design Elements in Biological Materials: Application to Bioinspiration. Advanced Materials, 27(37), 5455-5476

- Pearce (1980), Structure in Nature is a Strategy for Design, The MIT Press; Reprint edition

As always, I welcome all inputs and comments – if you have an example that does not fit into any of the 6 categories mentioned above, please let me know by messaging me on LinkedIn and I shall include it in the discussion with due credit. Thanks!